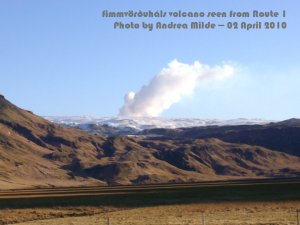

Last week two of us decided to go and see the volcano at Fimmvörðuháls in southern Iceland before it was too late. It began erupting around 21 March, and on Thursday last week reports were coming in that it was beginning to die down. But then that same evening a new fissure opened up, renewing the flow of lava.

Now the walk from Skógafoss up to Fimmvörðuháls and down the other side into the lush and wonderful valley of Þórsmörk is one that I’ve been wanting to do ever since I visited Þórsmörk last summer, but it’s not a walk you would ordinarily do at the start of April. Fimmvörðuháls is a watershed lying over 1000m up in between two glaciers, Eyjafjallajökull and Mýrdalsjökull. The weather can be very changeable, large sections of the route are liable to be snowed over, and it can be bitterly cold. I have heard that it has reached -30C up there in the last couple of weeks, and that several walkers have come down with hypothermia.

Fimmvörðuháls eruption seen from Route 1

It was cold. The roadside thermometers en route read -9C and I had to wear two woolly hats and a hood to keep my head warm. Without the hood, the wind just blasted through. I felt like an Arctic explorer, with just a small patch of skin exposed around the nose, which ended up getting super chilled and sunburnt at the same time.

The walk began at Skógafoss, an impressive waterfall known for its perma-rainbow (so long as the sun is shining). In the summer I’d tried to get as close to the rainbow as I could; the closer I had got, the more the rainbow had shrunk, until its arc had become a full circle just a metre or two from my hands. At that proximity to the falls, you feel like you’re being battered by shock waves as the force of water slamming into the pool at the bottom sends pulses of spray and water radiating outwards.

I got drenched, of course, but that was the summer. This time we made straight for the steps up beside the waterfall, which are a good warm-up for the walk to come. Above Skógafoss, the path climbs continuously but gently, following the river Skógá as it runs through ravines, around rocky outcrops, and over dozens of waterfalls. Several times the path splits, but the branches always re-join, so you can’t go wrong. The left branches usually pass closer to the river—more picturesque, but sometimes also involving precipitous scrambles.

In spite of the cold, the sun was bright and the sky absolutely clear, so we had fantastic views looking back down the mountainside towards the ocean, with flat farmlands and black sands in between. The river was often marked by a dark gash of canyon, and on the right the massive but diminishing pyramid shape of Raufarfell showed how far we had come.

snowboard heaven

Many of the waterfalls were frozen over, and overhangs in the canyon walls were dashed with giant icicles. Smoothly formed features in the upper rock strata that must have been formed by fluvial erosion gave us a sense of geological change, how the river must once have flowed much higher up in the canyon.

The river itself was frozen over in many places, with dark channels where the water still flowed freely marking the thalweg, the place where the current is strongest. Sometimes the shapes formed by the ice seemed to pick up the spiralling patterns of eddies, especially at turns and narrow points, and once or twice I spotted what looked like fast-forming ox-bow lakes, where the water must have been blocked off, only to push through another course.

After three hours or so, at about 550m, we came to the snowline, where it might ordinarily have become much harder to navigate, but because so many people had already hiked to see the volcano before us, all we had to do was follow the footprints. Every now and then we got overtaken by other walkers, who all seemed to know exactly where they were going, so by watching their progress we could see where the path was leading.

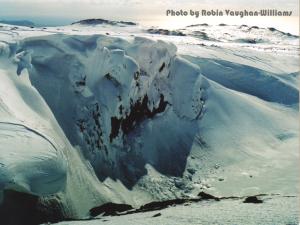

monster eggs hatching through the snow

Up in the snowfields, the landscape took on a completely different appearance. The incline became gentler around this point, and we were high enough to see far into the distance, over the rolling tops of hills. Sometimes black rocks broke through the snow, like monster eggs hatching after a winter’s gestation. Beneath the sun, the snow shone fiercely bright, and beyond we could still make out the wide strip of beach and the sea, which had turned orange near the horizon.

This was, however, the hardest part of the ascent. The plume of smoke issuing from the volcano seemed much closer now, and we kept thinking it was just beyond the next ridge, only to discover yet another plane to traverse. We were also getting pretty tired, and began to begrudge the helicopters that buzzed back and forth overhead every half an hour.

Fimmvörðuháls eruption site

Finally, after six hours, we made it. For a while the snow had been speckled with grey—fallout from the eruption—and within about a one-kilometre radius of the site the snow was covered with a light black ash. I let out a yell when I caught sight of something red streaming intermittently over the edge of a slope, thinking it was lava, but it turned out to be the ribbon of a safety barrier.

There was a black triangular hill ahead of us (which I take to be a peak marked as 1093m on the map) and a mound to the right of it which people were using as a viewing platform. Walkers, skidoos, quad bikes, and jeeps were congregating at this point, and a helicopter was on stand-by nearby.

splash of lava

From the mound we could see a plane below us with the fresh lava flow spread out across it. It had already cooled enough to turn black and didn’t seem to be moving, but there were huge clouds of vapour rising out of it, and a sense of constant activity, with little bursts and hisses and spouts of steam going on in the background. Having walked across plenty of old lava fields, with their jagged shapes, random protrusions, and tectonic cracks and folds, I could well imagine the furious metamorphosis that was going on inside.

Behind the lava flow was a ridge (probably Brattafönn, 1053m), and beyond this splashes of red lava were constantly being thrown up into the air, as if Jackson Pollock were hard at work on his latest creation. Except that artists like Pollock usually built up with painstaking care the impression of spontaneity, whereas here the emissions were genuinely chaotic, channelled only by the underlying regularity of natural processes.

I have seen some spectacular images of lavafalls, which must have been taken the other side of the ridge, where the lava drops into the steep-sided Hrúnagil valley, but we weren’t able to explore the eruption site any more, as we needed to get back to Skógafoss before nightfall. As a parting shot, once we had turned our backs to the volcano we were bombarded with a shower of volcanic grit, which drummed on our coats like hail.

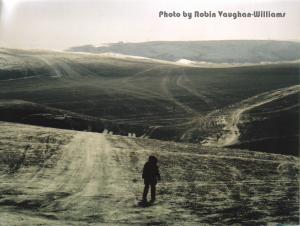

looking back

The descent was difficult, and took five hours, almost as long as the ascent. Clouds started rolling in while we were at the top, bringing fresh snow with them, and the snowfields we had to cross seemed to have become much more icy than on the way up, so that we both slipped over about 20 times and had to resort to taking tiny steps in order to avoid falling. We also both developed bad knees, so that even once we were below the snowline we pretty much had to hobble down the mountainside.

Twelve hours after setting out, we reached the car. It was 9.20pm, and within half an hour it was pitch black, with whatever moon there might have been obscured by the clouds. The peculiar thing was that on our way down we passed hordes of people walking up, even when we were halfway down. They seemed to think nothing of marching up a mountain with hours ahead of them, snow, ice, wind, sub-zero temperatures, and darkness descending, their only plan—to see how the earth had opened up.

patchy snow

Materials

- Find out about the weather at Fimmvörðuháls on this Danish weather site.

- 3D fly-through of the eruption area. This is the best way of getting an impression of the lie of the land I have found so far, although it misses out all the snow. Blue dots are cabins, and the fissures are in red.

- Video of a lavafall here, and some pretty nice footage of the eruption from Morgunblaðið here (listen out for the sounds…not just the music!).

- A couple of descriptions of the walk from Skógafoss to Þórsmörk can be found here (Bergverlag Rother) and here (Walk: The Magazine of the Ramblers). Bear in mind, though, that these are aimed at summer walks, not winter walks.

Posted in zqblog by Robin Vaughan-Williams, 5 April 2010.