I’ve been working with an aphasia group in Nottingham recently, which has thrown up some interesting challenges, as not everyone in the group can write well enough to be able to handle individual writing exercises. So I’m exploring alternatives like collaborative group poems and getting them to work in pairs.

Last week we had an inspiring session working on a collaborative poem to do with war. In the past, some of the best sessions I’ve facilitated have been the most spontaneous ones, which haven’t relied much on preparation and where the participants have had a lot of input into the content of the class or workshop. This was one of those sessions.

Last week we had an inspiring session working on a collaborative poem to do with war. In the past, some of the best sessions I’ve facilitated have been the most spontaneous ones, which haven’t relied much on preparation and where the participants have had a lot of input into the content of the class or workshop. This was one of those sessions.

We’d planned to base the session around memory and I’d prepared a number of exercises working with this theme. However, I’d just started explaining what we were going to do for the first exercise when, after barely two minutes had passed, the bells started ringing. It was 11am on Remembrance Day, 11 November, and we’d agreed beforehand we were going to observe the two minutes silence.

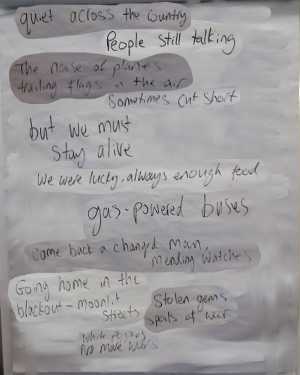

While we were sitting there quietly I started thinking this would make a great subject for the session, so when the silence was over I changed the plan and asked people what they’d been thinking about during the two minutes. I then got them talking in more detail about their thoughts or any memories they associated with war, and started writing lines up on the board based on what they were telling us.

We had a whole range of responses from very general sentiments about war to specific memories of childhood during the blitz and friends who’d served as soldiers. One woman remembered how she’d been lucky to live on a farm where there was plenty of food even during rationing. One man remembered someone who’d come back from service a completely different person, clearly traumatised, highly reclusive, but was able to find peace in mending watches.

Someone else had a bit of an adventure story from an uncle (I think), who’d been captured by the German army during WWII and held captive as a POW. One day they discovered loads of gems on a job they were doing and started hiding them in their pockets, but the soldiers found out and had them lined up against a wall to shoot anyone found with the stolen gems on them. I think they managed to ditch the precious stones just in time. And another person described how she lives near an airfield where Lancaster bombers still occasionally take off, and the Red Arrows practise their manouvres.

Once we had a selection of lines on the board, with something contributed by everyone, I asked the group to arrange the line order to form a poem. Which line comes first, which is second, and so on? We could easily have ended up with a disparate set of experiences, but the lines seem to gel and build upon one another, constructing a narrative out of different people’s thoughts and memories. There are also some nice examples of contradiction in the first verse, which show how contrasting sentiments can be combined for rhetorical effect.

‘Pegasus Bridge’

Quiet across the country

people still talking

the noise of planes trailing flags in the air

sometimes cut short

but we must stay alive.

We were lucky, always enough food

gas-powered buses

came back a changed man, mending watches

going home in the blackout—moonlit streets

stolen gems, spoils of battle

white poppies—no more war.

(by Frances, Paula, Beryl, Emma, Cliff, and the three Davids at Aphasia Nottingham, and myself)

Hello, I wondered if you could help? I am looking for a poem I read whilst visitind cafe Gondree at peg bridge. The poem was entitled Corp Smith.

I am planning to write a second book based on this poem. If I can find it?

Just wondered if you had a copy?

regards Mark G Nolan.